Adrian Scottow. Skin. Flickr.com, taken on June 20, 2010.

Lighter skinned people shed more dead skin than others: True or false?

I was asked this question this past Monday by one of the visitors to my site:

- Question: Why do some people have and shed more dead skin cells than others?

- Additional: This condition seems to be inherent in light-skinned, light haired people.

This is not something I knew the answer to, and I was excited to look into this. Of course, the first element was to determine if the question was based on a valid premise. Do light-skinned shed more dead skin cells than dark-skinned people?

I discovered information that I had not been aware of before.

In this article, I will walk you through the way I researched the topic, and my final conclusion (if you want the dessert without the main course, just go to the conclusion).

How do we produce dead skin cells?

The skin is a barrier covering the whole human body. An average adult skin surface area is 2 square meters (21.5 square feet) which is ~ the area of a dining table that seats 8 people.

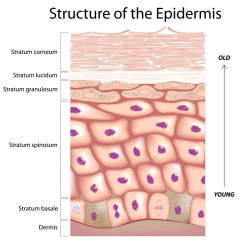

The skin is continuously proliferating, renewing itself every 27 days. The outermost layer of the skin is the epidermis ("sitting above the dermis"). And the epidermis' outermost layer is the stratum corneum. In this "horny" layer, the skin sheds continuously. In fact, the human body is estimated to shed 200,000,000 cells every hour (another estimate = 20 million cells/hour - 1).

Alila Medical Media. Epidermis of the skin. Shutterstock.com, ID: 125126000.

New skin cells are produced from the basal layer, as shown in the image, moving from young cells to old cells. As new cells are produced, they push the older cells to the surface. As the cells move away from the dermis, they flatten out and accumulate keratin proteins. When the cells reach the stratum corneum, they lose their internal organelles and nuclei. They are now flattened, diamond shaped, and stiff with keratin (2).

Note that the stratum corneum (the bright pink cells with no nuclei) is multiple layers of cells. In dark-skinned people, the number of layers is 21.8, whereas those of lighter-skinned people the number is 16.7 (3).

The cornified cells at the surface desquamate by breaking down connections between the topmost layer and the one below it. The connections between the cells remain relatively intact, allowing groups of dead skin cells to shed at one time (4, 5).

How do scientists measure how much dead skin we produce?

Various techniques have been used to measure the number of cells that are shed within a unit of time. These include placing a cup-type chamber over the skin and collecting the cells after 2 days; another technique is that of scrubbing the skin with a standardized machine; yet another is that of using a chemical (Dansyl chloride or silver nitrate) that is absorbed by the stratum corneum then measuring its disappearance over time (1).

Another method that seems intuitive is using a standardized tape method, where tape is placed on the skin and removed after 1 min (5). Finally, using a dermatoscope provides 10 x magnification of the skin allowing a visual estimate of how much desquamation of dead skin cells is taking place.

With these various techniques, scientists have estimated the rate of shedding of dead skin cells in various Ethnic groups (3, 5, 6, 8, 9).

Bachkova Natalia. Texture of women's skin close-up covered with small and large cracks and dead dry flaky scales after sun exposure. Shutterstock.com, ID: 1434471758

Why do we shed dead skin cells?

Before we go into that data, let me discuss why we shed skin cells in the first place.

Why does the skin shed its dead cells? What is the advantage? Why don't we just keep a layer of skin cells that remain attached to each other. After all, that is what some reptiles do. The cells remain attached and the whole layer of skin is shed at one time, when they molt.

The advantage for us is that the process of shedding continuously replenishes a strong water-repelling surface for the body. Here's what happens (2, 10): As the new cells are pushed upwards in the stratum corneum, they get stuffed with keratin, as I discussed above. In that process, the cells also package fat and enzymatic proteins into vesicles.

Those vesicles are pushed out of the cell as it ages, releasing both proteins and fat. As the cell becomes a keratin-studded corpse, the extracellular matrix of fat/protein create a water-repellent glue that is tightly bound to the dead cells.

Biological caulking material

It is as if the process of dying produces a glue-like caulking material that protects the underlying cells from dehydration and environmental insults. In a sense, the outermost layer of the skin (the stratum corneum) acts like a wall of brick (dead skin cells) and mortar (fat mixture). The cells and secreted fat/proteins bind to each other with strong links, sealing the skin. Furthermore, many of the proteins secreted from the cells into the intercellular space have antimicrobial properties (4, 11). A true protective epidermis.

Not only do the cells bind the secreted material to themselves. They also cross-link to each other via specialized bridges (corneodesmosomes). Over time, these protein bridges are broken down by the enzymes in the extracellular space. This allows the cells the ability to separate from the outermost layer of the epidermis and desquamate.

Darker colored skin ages at a slower rate than lighter colored skin

There are a number of factors that increase or decrease dead skin shedding. Diseases (such as psoriasis and eczema), Age, and environmental factors (sun exposure, winter conditions) and genetic factors all affect the rate of skin shedding.

However, all else being equal, older skin sheds more stratum corneum cells than younger skin (5, 7, 8). Which type of skin ages faster? Light-skinned or dark-skinned?

The stratum corneum of Caucasians has less layers and is less compact and less cohesive than that of darker-skinned individuals (16.7 layers versus 21.8 layers; 3, 7). Furthermore, darker skin types have greater lipid content compared to whiter skin types (7), presumably leading to a stronger glue between the cells. Also, light-skinned individuals are more susceptible to sun-induced damage. For dark-skinned individuals, the melanin in the skin protects from the aging produced by UV light. It is estimated that darker skin gives the person an intrinsic SPF-protection index of 13.4 (7).

The data is clear that the skin of light-skinned individuals ages faster than that of darker skinned individuals (7). Thus, you would expect that lighter skinned individuals will shed more dead skin cells than darker-skinned individuals.

sruilk. Macro of dry woman skin before and after moisturizing treatment. Detail with and without desquamation and exfoliation due to dehydration. Shutterstock. com, ID: 2027066501

What does the data say?

I looked at several articles to review shedding of dead skin cells by in different Ethnic groups. Here are the representative articles:

- Rawlings (3): evidence of greater desquamation index of Whites compared with blacks.

- Chu (5): African-Americans showed stronger intercellular bonding; there was less scaling on the forearms of older African-Americans compared to Caucasians. The desquamation was more prevalent with age.

However, there were contradictory results:

- Wesley (9): Blacks had a 2.5 times greater spontaneous desquamation rate compared with Caucasians and Asians

- Manuskiatti (8): Their results support age and anatomic site but not race as a significant influence on skin roughness and scaliness.

What can we conclude with all the above?

Conclusion: do lighter-skinned people shed more dead skin?

We can conclude three items from the data:

- Light-skinned individuals experience faster aging of their skin compared to dark-skinned individuals.

- As one grows older, there is more shedding of dead skin cells.

- The stratum corneum of dark-skinned individuals is more compact, exhibits more cohesiveness, and has more layers than light skinned individuals.

Based on those three factors, it is very likely that light-skinned individuals shed more dead skin cells (or have more scaling) than clinically similar dark-skinned individuals.

References:

- Roberts D, Marks R. The determination of regional and age variations in the rate of desquamation: a comparison of four techniques. J Invest Dermatol. 1980 Jan;74(1):13-6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12514568. PMID: 6985944.

- Murphrey MB, Miao JH, Zito PM. Histology, Stratum Corneum. [Updated 2021 Nov 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513299/#

- Rawlings AV. Ethnic skin types: are there differences in skin structure and function? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Apr;28(2):79-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00302.x. PMID: 18492142

- Eckhart L, Lippens S, Tschachler E, Declercq W. Cell death by cornification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Dec;1833(12):3471-3480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.010. Epub 2013 Jun 20. PMID: 23792051.

- Chu M, Kollias N. Documentation of normal stratum corneum scaling in an average population: features of differences among age, ethnicity and body site. Br J Dermatol. 2011 Mar;164(3):497-507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10120.x. Epub 2011 Jan 28. PMID: 21054338.

- Smith A. How do people from different racial groups age? Medical News Today, Sept 3, 2021 (Medically reviewed by Amin S).

- Vashi NA, de Castro Maymone MB, Kundu RV. Aging Differences in Ethnic Skin. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016 Jan;9(1):31-8. PMID: 26962390; PMCID: PMC4756870.

- Manuskiatti W, Schwindt DA, Maibach HI. Influence of age, anatomic site and race on skin roughness and scaliness. Dermatology. 1998;196(4):401-7. doi: 10.1159/000017932. PMID: 9669115.

- Wesley, N.O., Maibach, H.I. Racial (Ethnic) Differences in Skin Properties. Am J Clin Dermatol 4, 843–860 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200304120-00004

- Yousef H, Alhajj M, Sharma S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. [Updated 2021 Nov 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/

- Bosko CA. Skin Barrier Insights: From Bricks and Mortar to Molecules and Microbes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jan 1;18(1s):s63-67. PMID: 30681811.